Updated Wednesday 19 July 2018

Zero Invasive Predators Ltd (ZIP), with the support of the Department of Conservation (DOC) and Predator Free 2050 Limited, is currently undertaking a programme of research and development work in the Perth River valley on the West Coast of the South Island.

The purpose of the work is to test and refine an approach to completely remove possums from large areas and prevent them from re-establishing, and to develop this approach for ship rats and stoats. We call the approach ‘Remove and Protect’. This is the first time such an attempt has been made on the New Zealand mainland. The results are expected to help enable New Zealand to achieve predator-free status by 2050.

The Perth River research area contains kea, which is a nationally endangered species. The purpose of this Update is to outline some new measures that we are progressing to mitigate potential impacts on kea of the work underway in the Perth River research area.

Background

Kea are the world’s only mountain parrot and considered by scientists to be one of the most intelligent bird species in the world. The national population of kea is expected to decline by 50-70% over the next 10 years unless the causes of decline are addressed. Predation by introduced predators like possums and stoats is considered one of the key reasons for the decline in kea numbers.

One component of ZIP’s ‘Remove and Protect’ approach that is being tested and refined in the Perth River research area is the use of a method called ‘1080 to Zero’ to completely remove predators.

Predator control using aerial 1080 has an overall beneficial impact on kea nesting success. In one recently published study, kea nest survival at a monitored site increased from 46.4%, before the application of 1080 to 84.8% after the application of 1080 (Kemp et al. 2018).

However, kea have an inquisitive nature, and some kea have died as a result of 1080 poisoning. Consequently, from its inception, the research and development work programme in the Perth River valley has actively considered ways to reduce risk to kea.

Steps already taken to reduce risk to kea in the Perth River research area

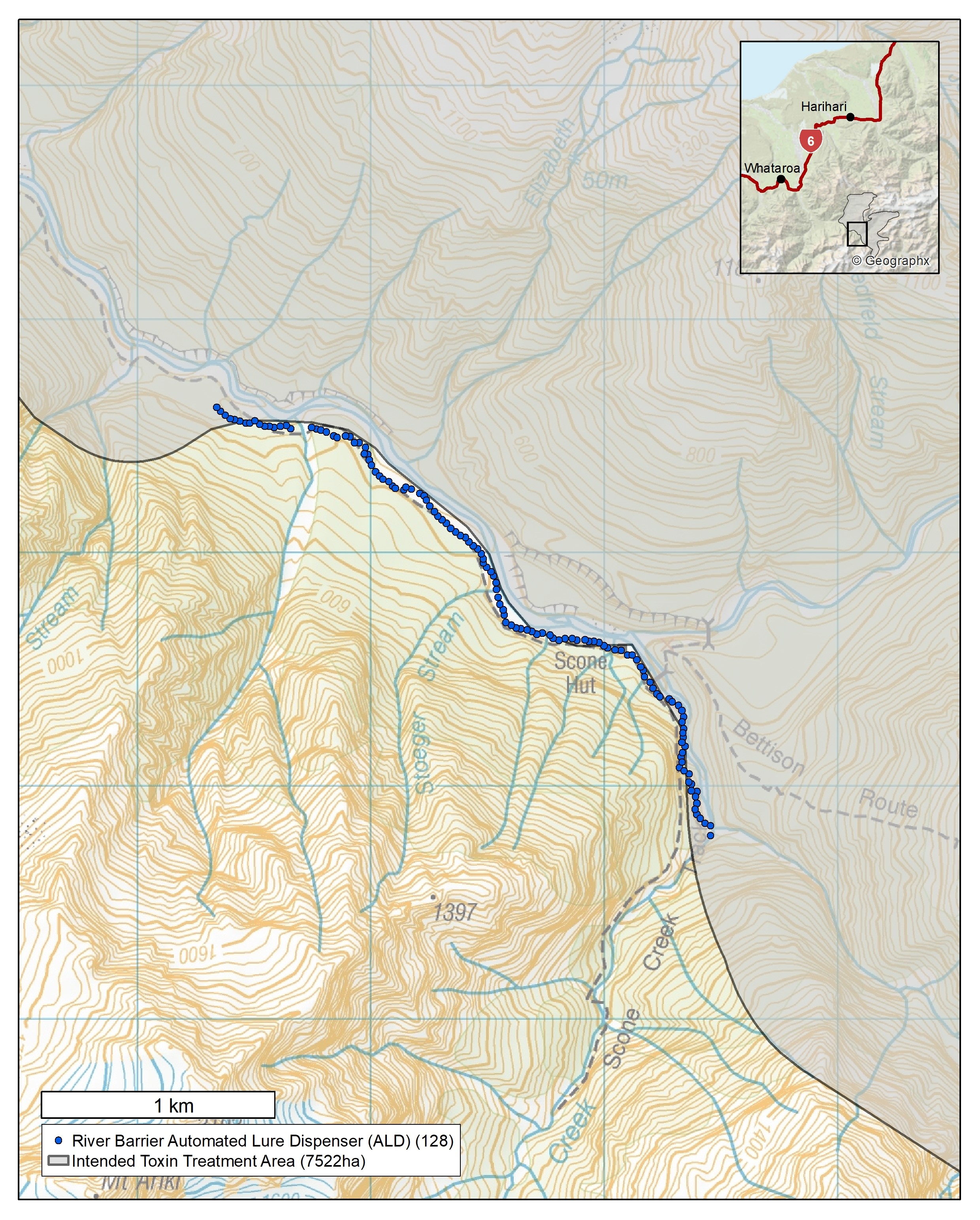

Minimising the risk to kea was part of the decision making process when it came to deciding the location of the Perth River research area. We reduced the size of the original proposed research area from c.20,000ha to 12,000ha, to lessen the number of kea exposed to 1080 baits (the 1080 to Zero treatment area is only 7,500ha).

The research area was located as far as possible from the nearest kea scrounging site, Franz Josef township, which is 28km away at its closest point. We also selected an area that had a history of aerial 1080 operations – in this case five operations since 1997. The site was also selected on the basis of a number of other criteria related to our research requirements.

Since then, 30 kea have been fitted with radio transmitters (and another 25 have been banded) to monitor the impact of applying aerial 1080 on kea mortality and breeding success. Radio-tagged kea are scheduled to be monitored (using a light aircraft) after each application of prefeed and toxic bait. Monitoring was done after each of the two prefeeds that were applied on 30-31 May and 21 June.

We also recently completed a project to estimate how likely kea would be to consume baits, in order to assist DOC to decide whether the toxic bait application should proceed. In summary, the results confirmed what was already known - i.e. that kea interact with bait. However, owing to the small sample size, it was not possible to make a specific estimate of the likely level of actual consumption of toxic bait.

Two new measures to mitigate potential impacts on kea

It was originally estimated that around 18 kea were likely to be present in the research area. During the course of our work, we discovered that there is a healthy population of approximately 75-100 kea in the research area. It is likely that the current population of kea can be partly attributed to the benefits of the previous five applications of aerial 1080 in the area.

We are committed to doing all we can to reduce the risk of kea mortality in the event that the decision is made to apply aerial 1080. Recently we have initiated two new measures to help achieve this.

Discourage kea from eating 1080 bait

To reduce the risk of birds consuming toxic bait, we are attempting to enable kea to learn that eating bait is not good for them, by applying non-toxic prefeed bait containing a repellent, anthraquinone, that makes them feel sick, before any toxic bait is applied.

Anthraquinone is a secondary repellent in that it has no smell or flavour, but makes birds feel sick after consumption. By associating the bait with the source of illness, birds will be less likely to eat it in future.

On Saturday 14th July, with the permission of the Department of Conservation, green-dyed baits laced with anthraquinone were applied within a thin band along a section of the alpine boundary of the research area.

This non-toxic bait was dyed green, in order to resemble the toxic bait as closely as possible.

We may reinforce any repellent effect with a repeat application of repellent bait, immediately prior to toxin baiting. The thinking behind doing this is that the more times kea have the opportunity to learn to avoid the bait, the greater the chance that they will avoid it in future.

Provide tahr carcasses as alternative food/distraction

Our field staff have observed, and there is substantial anecdotal evidence, that kea in this area already quickly locate and utilise dead tahr (either left by hunters or dead from natural causes) as a food source.

On Friday 29 June, the carcasses of 21 tahr shot by a DOC ranger (using a high-powered rifle – not lead shot), as part of a DOC’s wider programme of tahr control, were placed at approximately 1km intervals along the upper boundary of the 1080 to Zero treatment zone, in order to lure kea away from the baits.

Kea activity at each tahr carcass is being monitored using trail cameras, in order to help us understand whether this approach plays a role in limiting any impact from the aerial operation. Our staff have already observed a number of birds visiting the carcasses.

There is strong evidence to suggest that the risk to kea of secondary poisoning (i.e. from eating the meat of animals that have been poisoned by baits) is much lower than the risk of primary poisoning (i.e. from eating baits) following an aerial 1080 operation (van Klink and Crowell 2015).

Furthermore, it is not known if aerial 1080 impacts tahr. This is being investigated as part of a Game Animal Council-led project connected with the proposed aerial operation in the Perth River research area.

We will continue to record activity at the tahr sites from now until any toxic bait is rendered safe. From this data, it should be possible to determine whether or not the kea maintain interest in the tahr carcasses in the presence of bait.

Final thought

DOC is currently reconsidering the permission for ZIP to apply aerial 1080 as part of the Perth Valley research project.

Ultimately, the decision about whether to apply aerial 1080 in the research area will balance the risk of individual kea mortality against the potential population benefits to kea (and other native species) in the research area, as a result of predator removal, and the benefits of continuing to test, refine and develop the Remove and Protect approach and its potential contribution to a Predator Free New Zealand.

We will continue to provide updates via the ZIP website as this work progresses.