Background

When the virtual barrier was installed at Bottle Rock in November 2014, stoat defences were not included as we did not believe that the 400 ha peninsula was large enough in relation stoats' speed or 'typical' home range size (60 – 200 ha) to confirm the area was free of stoats at any point in time. Our suite of control tools for stoats was also extremely limited; we were reliant on TUN200s baited with fresh rabbit meat, Erayz or eggs. Additionally, the monitoring methods available to us at the time were too insensitive to determine the presence of stoats in the landscape at very low density. For example, stoats may be present even when tracking tunnels show zero stoat tracking.

However, the virtual barrier system caught a surprisingly large number of stoats (25) during the 2014 beech mast (lured with mice caught in mouse traps inside TUN200 boxes), and another 11 following the rat and possum removal. This gave us some confidence that it would be worthwhile to begin trialing stoat defences at Bottle Rock.

Trial objectives:

Observe stoat mobility to help inform configuration of the stoat 'barrier' and detection system

Test first iteration of stoat 'barrier'

Investigate the effectiveness of cameras when lured with bedding material from female stoats in oestrous (on heat)

Method:

Tim Sjoberg, Predator Behaviour Technician, holds a stoat fitted with VHF collar for release at Bottle Rock.

Stoat defences were installed into the first, third and seventh lines of the virtual barrier, as follows:

D1: TUN200 baited with Erayz @ 20 m spacing

D3: TUN200 baited with fresh rabbit meat and egg @ 20 m spacing

D7: TUN200 baited with oestrous stoat bedding @ 40 m spacing

Wild stoats were caught near our predator research facility in Lincoln, fitted with VHF collars, and transported to Bottle Rock where they were released in the protected area.

Three successive releases were carried out, the first two with three stoats each, released at different points around the Bottle Rock coast line.

20 cameras were set up on a 20 ha grid and lured with oestrous stoat bedding in a tree-mounted wire mesh tea strainer and ‘chew cards’ containing ground rabbit kidney.

Stoats in the second and third releases had their fur dyed with a non-toxic hair dye for easy identification in camera footage.

Sky Ranger was then used to track stoat movements every 3-5 days. This was done via a VHF 'fix' at a point in time rather than GPS tracking, so the dotted lines between den sites represent the minimum distance possible between VHF fixes.

Results:

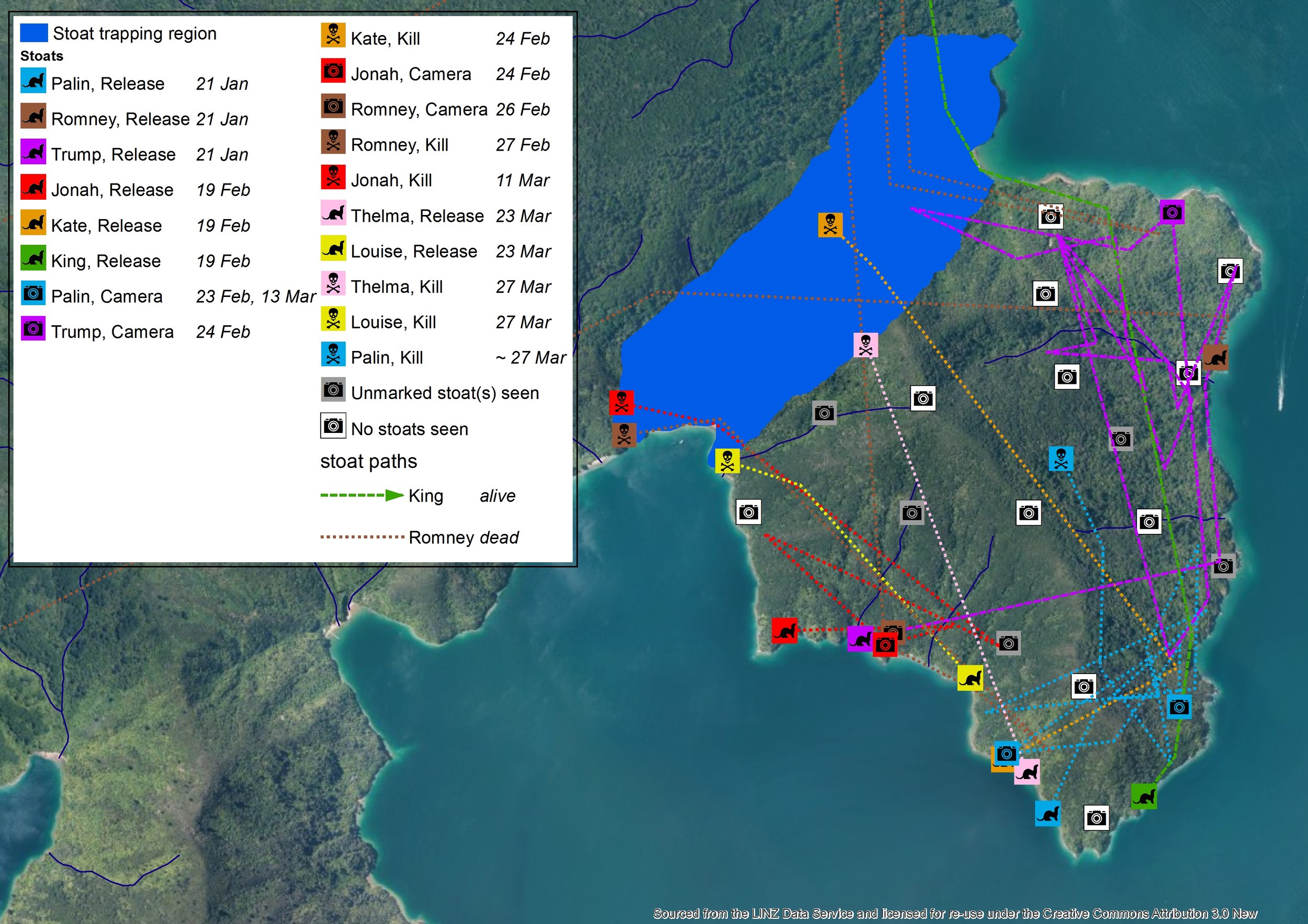

Map of movements of all stoats released on Bottle Rock as at 23 March 2016

All stoats were tracked successfully. The majority of stoats exhibited residential rather than exploratory/ roaming behaviour within a relatively short period of time following release. Only two stoats exhibited roaming characteristics – 'King' and 'Romney'. The fastest stoat, 'Romney', traveled a distance of 3 km in 4 hours; however <1 km per day was typical.

Map of movements of all stoats released on Bottle Rock as at 23 March 2016. As you can see, 'Romney' passed through the virtual barrier at least four times before being caught!

What did we learn?

'Jonah' interacts with oestrous bedding lure on camera (NB: in this video lure is on ground, probably having been removed from tree by a weka)

Camera detection appears to be our most sensitive stoat detection tool to date, with more than half of the stoats detected within a week of release. However, we were concerned that the cameras used may have deterred some stoats from interacting with the lures presented, possibly due to emitting infrared light, sound, or a combination of the two. We are now working with Don Peat of Kinopta and Professor Donald Bailey of Massey University to develop a ‘quiet’ camera that we hope will be unnoticed by stoats in the environment.

Oestrous stoat bedding appears to be a powerful lure but needs to be used only in a kill device, as stoats are unlikely to revisit it. Unfortunately, attempts to synthesise this lure have been unsuccessful, so we are also reliant on a very limited supply of the natural product (sourced from stoats at our research facility in Lincoln).

We intercepted 60% of stoats on their first encounter with the virtual barrier, but its effectiveness may have been compromised given that the majority of stoats released on the peninsula had already encountered oestrous bedding in the camera detection network. Additionally, stoats' willingness to interact with the oestrous lure more than once may have been influenced by the fact that the bedding material used for all devices had been sourced from a single female.

The last two stoats to be released, 'Thelma' and 'Louise', ran into the barrier very quickly, where they were caught in oestrous-lured traps. We suspect they did not encounter this lure in the detection system as neither stoat was picked up on camera.

We intend to release another 10 radio-collared stoats on the peninsula this summer, and oestrous bedding will not be used as a camera lure during this repeat of the trial.

Given what is generally understood about stoats' solitary nature and large home ranges, we were surprised that the stoats released did not cover, or attempt to cover, more ground. We also anticipated that the high density of stoats on the peninsula would have 'forced’ more to spread out and attempt to pass through the barrier rather than exhibiting the localised behaviour we saw in this trial.